Intro:

If you’re accessing this podcast, you’ve already listened to Rounders: A History of Baseball in America, our main show, and signed up as an exclusive email subscriber. Thanks so much for continuing to support both of these projects.

Note: A new episode comes out on Thursday (for paid subscribers)! I’ve been researching and recording some interesting topics I think you’re going to enjoy.

January 15, 1942: When Baseball Lit Up the Night: FDR’s Green Light Letter

On January 15, 1942, in the midst of World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt made a decision that would have a lasting impact on the sport of baseball.

In what would become known as the "Green Light Letter," FDR wrote to Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the Commissioner of Baseball at the time, stating that baseball games needed to continue because it was a morale booster and a welcome distraction for a nation at war. He even encouraged more night games so that war workers could attend after their shifts.

He also mentioned that baseball games, which typically last around two to two and a half hours, provided affordable recreation.

January 16, 1970: Curt Flood’s Lawsuit: A Game-Changer for Baseball

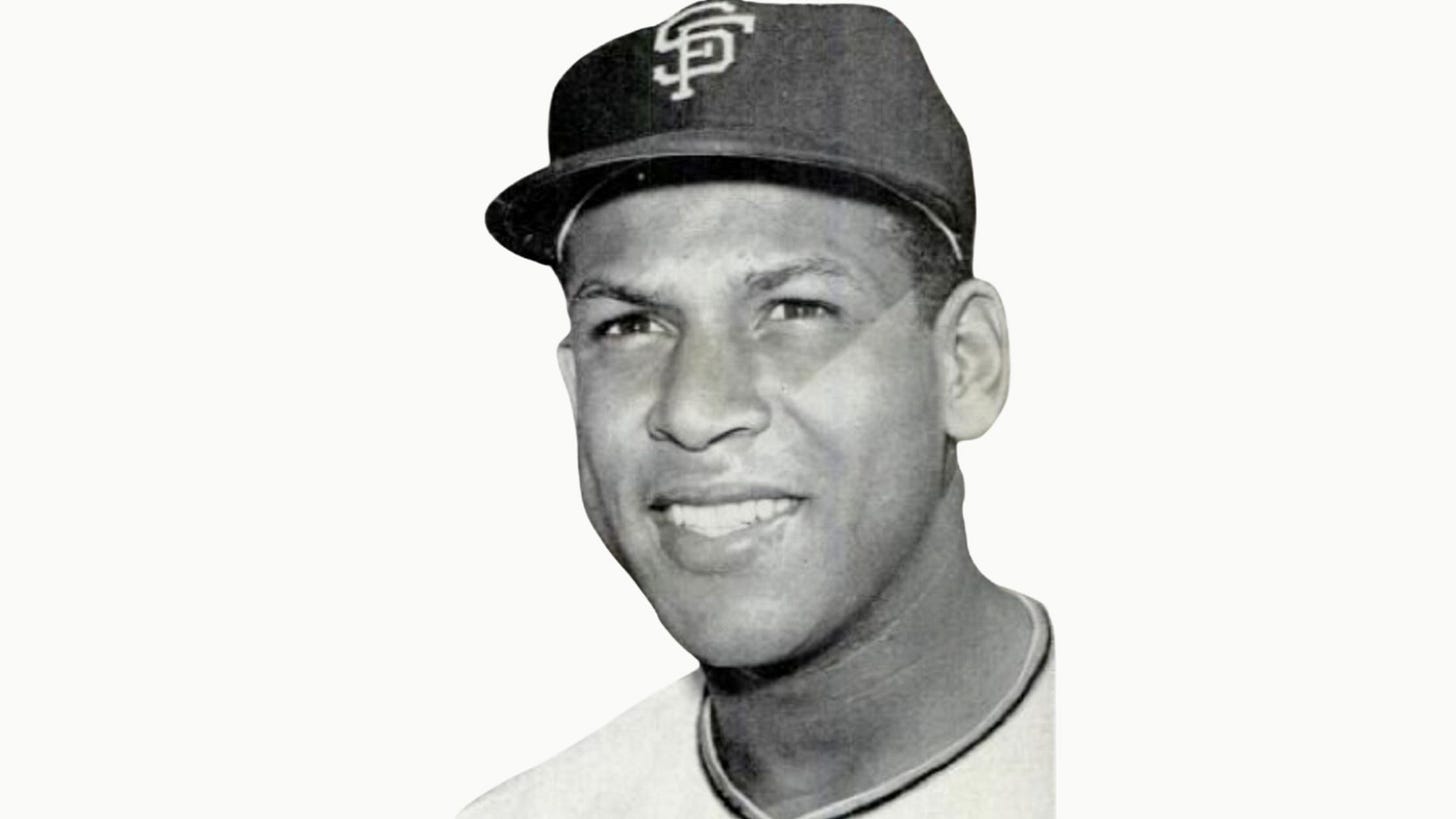

On January 16, 1920, Curt Flood, a Gold Glove outfielder, filed a civil lawsuit challenging baseball’s reserve clause. The reserve clause was a rule that bound players to their teams indefinitely.

Flood’s lawsuit was in response to a trade that sent him from the Cardinals to the Phillies. He refused to report to his new team, contending that the reserve clause violated federal antitrust laws.

Flood, who was then making $90,000 per season, sought $1 million in damages. His lawsuit, known as Flood v. Kuhn, began on May 19, 1970, before Judge Irving Ben Cooper at U.S. District Court in New York.

Despite the lawsuit being ultimately unsuccessful, it marked the beginning of the end for the reserve clause and laid the groundwork for the advent of free agency, forever altering the power dynamics in professional baseball.

January 17, 1960: The First MLB Player from Jamaica is Born

Charles Theodore "Chili" Davis was born on January 17, 1960, in Kingston, Jamaica. He is the first ballplayer born in Jamaica to appear in an MLB game.

Davis started playing baseball when he moved to Los Angeles from Jamaica at the age of ten. He was an outfielder and designated hitter from 1981 to 1999 for several teams, including the San Francisco Giants, California Angels, Minnesota Twins, Kansas City Royals, and New York Yankees.

Davis was a switch-hitter and threw right-handed. In his 19-year career, Davis was:

A .274 hitter with 350 home runs and 1,372 RBI in 2,436 MLB games.

He was a three-time All-Star (1984, 1986, 1994)

A three-time World Series champion (1991, 1998, 1999).

After his playing career, Davis also coached for the Boston Red Sox, Chicago Cubs, and the New York Mets.

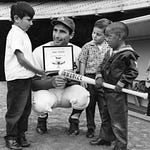

January 18, 1973: Orlando Cepeda Pioneers the Designated Hitter

On this date, Orlando Cepeda made history by becoming the first major league player signed expressly to become a designated hitter. This occurred just days after the American League approved the new designated hitter rule.

Cepeda, who had been released by the Athletics following the 1972 season, agreed to a one-year contract with the Boston Red Sox.

He was a veteran slugger with 15 major league seasons behind him, but had been hobbled by painful knee injuries for several seasons. Despite his physical challenges, he was ideally suited to perform exclusively as a hitter.

He recalls, “When the Red Sox called asking me about being their designated hitter, I didn’t know what they were talking about. I said, ‘What’s a designated hitter?’ There had never been such a thing in baseball. With my knees, I couldn’t run but I knew I could still hit. It was a great thing for me”.

Cepeda's signing with the Red Sox didn’t just introduce the role of the designated hitter - it also extended the careers of players like Cepeda who could still contribute offensively despite physical limitations.

Cepeda was elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee in 1999. For long-time Red Sox fans, he will always be remembered as their first designated hitter.

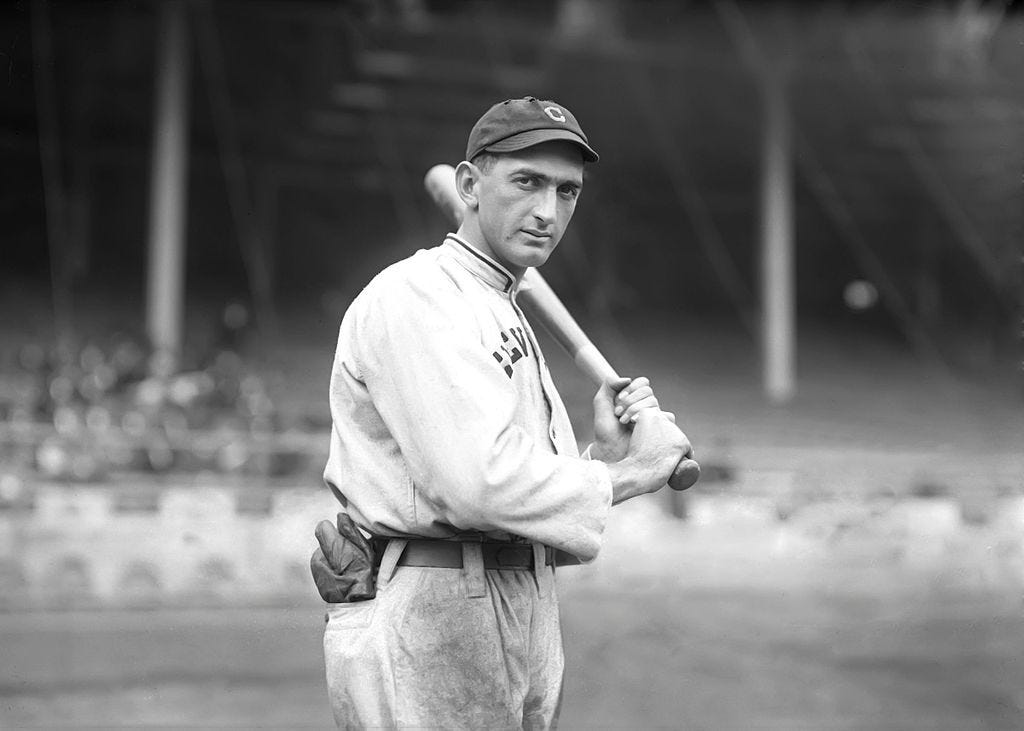

January 19, 1934: Shoeless Joe Again Denied Reinstatement

Shoeless Joe Jackson, one of the eight members of the Chicago White Sox expelled from organized baseball for conspiring to lose the 1919 World Series, appealed for reinstatement. The appeal was addressed to Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the first Commissioner of Baseball at the time.

Landis was known for his firm stance against corruption in baseball, and denied Jackson's appeal. This decision was in line with Landis' previous actions, as he had repeatedly refused reinstatement requests from the players involved in the Black Sox Scandal.

Landis' decisions, including this one, were often controversial, and supporters of Jackson still contend that he was overly harsh.

Despite the controversy, Landis' actions played a crucial role in restoring public confidence in the game. His refusal to reinstate Jackson underscored his commitment to maintaining the integrity of baseball. This event is a stark reminder of the consequences of the Black Sox Scandal and its impact on the players involved.

January 20, 1984: In a move that stuns New York fans, the White Sox draft Tom Seaver as compensation for losing Type A free agent Dennis Lamp to the Blue Jays. The Mets left Seaver off their protected list, erroneously assuming that no team would want to select the aging star. He will win his 300th game in a White Sox uniform in 1985.

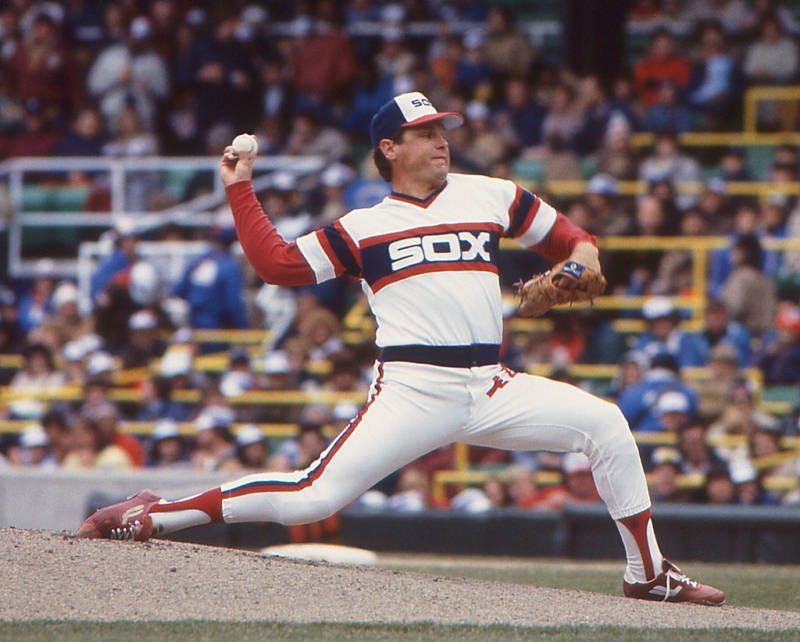

January 20, 1984: Tom Seaver Becomes the Unexpected White Sox Draftee

The Chicago White Sox made a move that left New York fans in disbelief in the 1984 free agent compensation draft. They drafted Tom Seaver, a star pitcher for the Mets and an eventual future Hall of Fame pitcher.

So, what was the controversy? New York had the chance to put Seaver on their protected list to ensure no one else took him, but they left him off under the incorrect assumption that no team would want to select the aging star.

Seaver, who was then 39 years old, was still a highly effective pitcher. Despite his age, the White Sox saw value in him and decided to draft him.

This decision was met with surprise, especially among New York fans, as Seaver had been a key player for the Mets. Seaver even stated he might file a lawsuit and not attend a training camp in Chicago. He eventually did, though.

In 1985, while wearing a White Sox uniform, Seaver achieved a significant milestone by winning his 300th game. This achievement further validated the White Sox's decision to draft him and demonstrated Seaver's enduring skill and value as a player.

January 21, 1960: A Lesson in Humility: Stan Musial Takes a Pay Cut

In 1960, a remarkable event unfolded in the world of baseball that would forever be remembered as a testament to humility and integrity. Stan Musial, a renowned player for the St. Louis Cardinals, did something that was almost unheard of in the sports industry. He asked for a pay cut, reducing his salary from $100,000 to $80,000 a year.

Musial believed that his performance in 1959 did not warrant the high salary he was receiving. He felt he had been overpaid in 1957 and 1958 and insisted that his salary should reflect his recent performance. This act was a stark contrast to the common narrative of athletes negotiating for higher pay.

Stan Musial’s request was granted, and his salary was reduced. This event stands as a powerful reminder of Musial’s character and integrity. His actions demonstrated a level of self-awareness and responsibility that is rare in any field, let alone the competitive world of professional sports.

Hold on a Second!

You get:

The ad-free version of 'Rounders' a whole DAY EARLIER.

A sneak peek at our secret list of upcoming episodes.

A chance to share your thoughts, which I might just read out in the episode.

Exclusive chats, events, and more fun stuff only for our members.

And if you're feeling extra awesome, join our 'Starting Nine' crew. Help shape the show, pick episode topics, and even get a shoutout as a producer.

Let's make 'Rounders' the top baseball history show together!

Share this post